This story in the National Catholic Reporter is interesting:

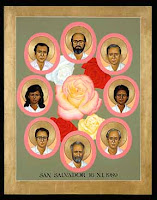

The Associated Press reported Nov. 17 that Archbishop Fernando Sáenz Lacalle spoke out against a criminal complaint filed last week in the Spanish High Court naming 14 members of the Salvadoran military and the nation’s president, accused of masterminding and covering up the assassination of six Jesuit priests, their housekeeper and her 16-year-old daughter at a San Salvador Jesuit university in November 1989. Lacalle was quoted, “El Salvador’s affairs should be resolved in El Salvador.”

With all due respect, Bishop…are you bloody kidding me? How can you not stand up for your brother priests when they were clearly killed in cold blood? How can any of your priests ever place their trust in you again? How can anyone who works for a University, much more a Catholic institution ever take you seriously?

Fr Joseph O’Hare the former President of Fordham preached an awesome homily only days after the tragic event took place. Here is an exerpt:

For the Jesuits of the United States, most especially those working at the 28 Jesuit colleges and universities in this country, there is an added sense of solidarity with the martyrs of last Thursday, based on the common identity of Catholic universities throughout the world. In eliminating the rector and vice-rector and some of the most influential members of the faculty of the University of Central America, the assassins cut out the heart of one of the most respected intellectual institutions in the country. As you know from newspaper accounts, these men were not merely murdered, but in a gesture of deliberate contempt, their brains were spilled out on the ground by their murderers. This chilling symbol was to demonstrate the power of bullets over brains. It represents the contempt of men of violence for the power of the truth.

There are those who have said, and who will say in the days and weeks ahead, that the Jesuits in El Salvador were not disinterested academics, that they had deliberately chosen to insert themselves into the political conflict of their nation. If they had remained within the insulated safety of the library or the classroom, their critics will charge, if they had not “meddled in politics,” their lives would not have been threatened.

But such criticism misunderstands the nature of any university, and most certainly the nature of a Catholic university. No university can be insulated from the agonies of the society in which it lives. No university that identifies itself as Catholic can be indifferent to the call of the church to promote the dignity of the human person.

Pope John Paul II, himself a man from the university world, has often challenged Catholic universities to confront the crucial issues of peace and justice in our world today. On his last visit to this country in September 1987, the Pope called on Catholic universities to recognize the need for the reform of attitudes and unjust structures in society. He spoke of the whole dynamic of peace and justice in the world, as it affects East and West, North and South: “The parable of the rich man and the poor man is directed to the conscience of humanity, and today in particular, to the conscience of America. But conscience often passes through the halls of academe, through nights of study and hours of power.” Again last April in his address to the Third International Congress of Catholic Universities, Pope John Paul insisted that a Catholic university must measure all technological discovery and all social development in the light of the dignity of the human person.

It was this distinctive mission of a Catholic university that inspired the Jesuits of El Salvador to seek, not only through teaching and writing, but also through personal interventions, a resolution of the terrible conflict that has divided their land. Those of us who carry on this mission of faith and justice in the relatively comfortable circumstances of North America can only be humbled by the total commitment to the ministry of truth that stamped the lives of the Jesuit scholar teachers of El Salvador and in the end cost them their lives.

This liturgy is not the time for political analysis or political advocacy. At the same time, we would not be faithful to the truth of this moment if we did not recognize than another more troubling source of our solidarity with the people of El Salvador is the history of the last 10 years, in which the Government of the United States has worked closely with the Government of El Salvador. The policy of the United States toward El Salvador, in theory at least, has had respectable objectives: to control extremist forces on left and right, to encourage an environment in which the people of El Salvador can choose through democratic process the government they wish. But our Government has also insisted that massive military assistance to the Government of El Salvador is necessary to achieve these goals.

Before his assassination in 1980, Archbishop Romero has written to President Jimmy Carter asking him to curtail American military aid to the Government because, in Archbishop Romero’s opinion, such aid only escalated the level of violence in that country and prevented the achievement of a negotiated political settlement. Now, nearly 10 years later, can anyone doubt the accuracy of Archbishops Romero’s warning? Does anyone believe that the national security of the United States can possibly be endangered by the results of the civil war now raging in El Salvador? At a time when our Government leaders and our corporate executives hasten to socialize with the leaders of the Communist giants elsewhere in the world, why must we assemble our military might to deal with revolutionary movements in tiny Central American nations? Are our national interests really at stake? Or are we obsessed with the myth of the national security state, a myth that is discredited each day by events elsewhere in the world? After 10 years of evasions and equivocations, a tissue of ambiguities, the assassinations of Nov. 16 pose, with brutal clarity, the question that continues to haunt the policy of the United States toward El Salvador: Can we hand weapons to butchers and remain unstained by the blood of their innocent victims?

The final word of this liturgy cannot be one of anger or denunciation. It must be one of hope. For this too, in the end , is the ground of our solidarity with the people of El Salvador. If Jesuits are men crucified to the world and to whom the world is crucified, it is only because we believe that out of the crucifixion of our Savior, El Salvador, came life and comes life. With the people of El Salvador we believe in the words of Jesus cited in today’s Gospel: “Unless a wheat grains falls on the ground and dies, it remains only a single grain; but if it dies, it yields a rich harvest: (Jn. 12:24).

When Christians celebrate the Eucharist, they take the bread, break it and remember Him who took His life, broke it and gave it that others might live. With deep hope in the Resurrection of the Lord, we pray that the final word in the drama of El Salvador be one of life and hope rather than death and despair. We pray that the irony of that tiny tortured country’s name, El Salvador, will be redeemed by the resurrection of its people.

AMERICA December 16, 1989

We, in the United States, know all too well about murderous madmen who hope to surpress ideas with violence. We’ve seen that in the violence of September 11th. We’ve seen it in the nihlistic shootings of Columbine and more recently Virginia Tech. We see it each day another bullet is fired in anger towards someone because of what they think, proclaim or stand for.

When we don’t stand for justice, that, my friends, is not freedom talking. More importantly, it is not the freedom that God gives us that hinders tongues. It is merely fear, perhaps even well meaning fear. Listening to fear is often a safe route–we don’t merely throw caution to the wind, after all. But faith indeed is the opposite of fear. Faith is listening to the voice of God, the voice of wisdom, the voice of truth.

The Jesuits of El Salvador listened to that voice, a voice that called them to justice for the Salvadorian people. It was that voice that people in power found so dangerous. Thoughts so profound that the poor began to think that maybe their lives were indeed worth living–that they indeed counted, that they could be more than oppressed members of a society that tried to keep them down with injustice.

That voice was indeed Jesus—who gives voice to the voiceless and hope to those without hope.

It is a dangerous voice to listen to…and if you do. It just might get you crucified.